We think of a road trip today as several hours by car. During the Revolutionary War, there was another road trip on horseback, taken by men from various states. And it ended up in a battle on Kings Mountain. Once again, this will be celebrated 243 years after the battle this weekend.

The Tory commander Patrick Ferguson started out with four regiments of Tory soldiers from New York, New Jersey and Connecticut. Along the way he recruited other men from the South Carolina countryside.

Patrick Ferguson

Some of the South Carolinians who joined Ferguson were loyal to the crown. Some of them fought with Ferguson because they thought the British would win the war. Some were forced to join at gunpoint.

As Ferguson’s army moved into North Carolina, he heard about the many Scotch-Irish immigrants who had crossed the mountains in defiance of King George III’s Proclamation of 1763. In September, he issued a written warning to the frontiersmen to lay down their arms or he would “lay waste to their country with fire and sword.”

Isaac Shelby, a leader in what is now Sullivan County, Tennessee, received this warning. He rode to meet with John Sevier, who was in Jonesborough at the time. Shelby and Sevier decided to try to raise an army that would link up with other rebellious forces and fight Ferguson before he moved west.

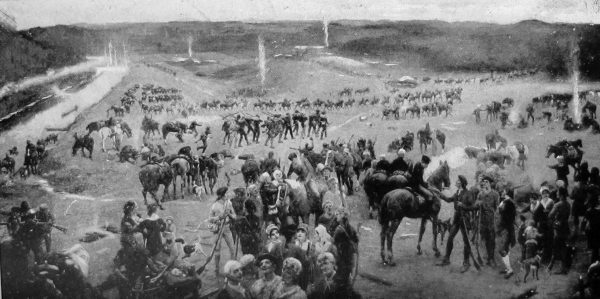

“Gathering of Overmountain Men at Sycamore Shoals,” a painting by Lloyd Branson

On September 25, these men gathered at the Sycamore Shoals of the Watauga River (present-day Elizabethton). On that day Sevier and Shelby arrived with 240 troops each to join Col. Charles McDowell, who was already there with 160 North Carolina riflemen. They were heartened when Col. William Campbell marched in with 400 Virginians. On 30 September the American force reached Quaker Meadows in Burke County, where it was joined by Col. Benjamin Cleveland and 350 North Carolinians. Most of these men had no military training. None of them had uniforms. Some didn’t even have shoes!

But they were skilled with rifles. Many had previous experience fighting against Native Americans. And they were furious at Ferguson for issuing such a threat.

While waiting for all to gather, they tended their horses, mended clothing and equipment, and prepared food such as parched corn and beef jerky. The men cleaned their rifles and mined lead from the hillsides for making “shot” or ammunition. At Sycamore Shoals, they received from Mary Patton 500 pounds of gunpowder she had made at her own powder mill.

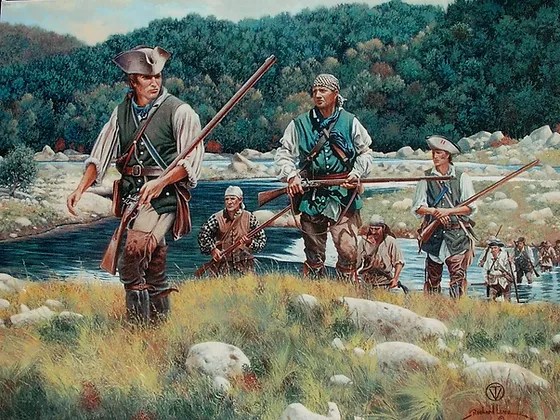

These men said goodbye to their wives, their sons and their daughters, not knowing if they would ever see them again. They marched, walked and rode 330 miles in two weeks to surround Ferguson and his men on top of a sixty foot hill.

Colonel William Campbell brought his Virginia militia to join the others, and the commanders chose him as their officer of the day. He told his men “to shout like hell and fight like devils.” Others fell into this group until the number was 910 Patriots facing 1100 Tories. This was a fight between two groups of Americans; Patrick Ferguson was the only British officer.

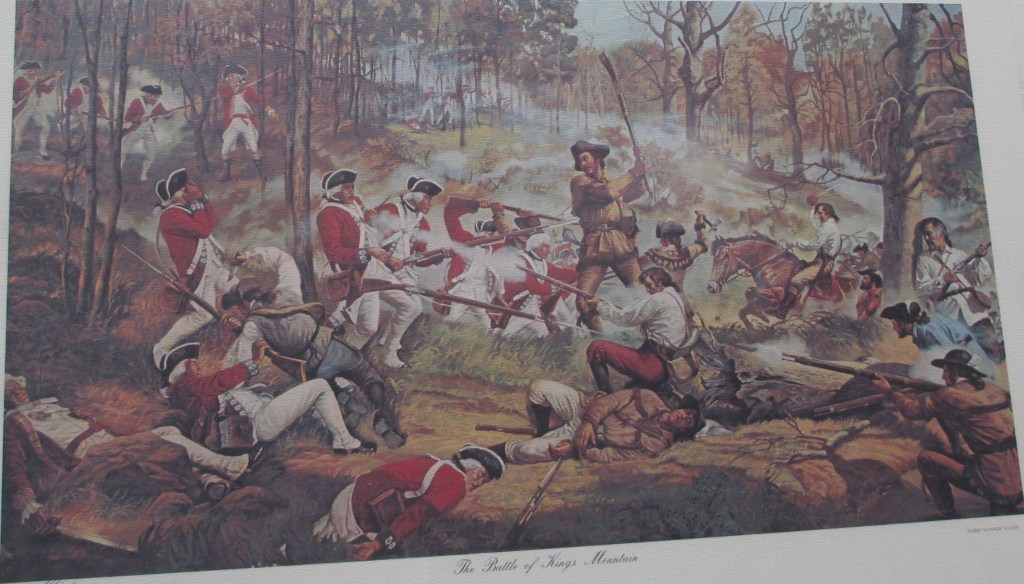

A rainy day and night before the battle didn’t deter them. The men quietly surrounded the hill and attacked from all sides. The patriot forces yelled at the top of their lungs and charged up the hill. They fired, ducked behind the nearest rock or tree to reload, and fired again. They used tactics they had learned from fighting Native Americans on the frontier.

Ferguson’s men fired, and reloaded, and fired again. On at least two occasions, his men affixed bayonets to their rifles and charged down the hill. The Overmountain Men (who didn’t have the types of rifles on which bayonets can be afffixed) ran from the bayonets. But after Ferguson’s men headed back up to defend the top of the hill, the rag-tag army chased them.

James Collins wrote:

“We were soon in motion, every man throwing four or five balls in his mouth to prevent thirst, to be in readiness to reload quick. The shot of the enemy soon began to pass over us like hail; the first shock was quickly over, and for my own part, I was soon in a profuse sweat. My lot happened to be in the center, where the severest part of the battle was fought. We soon attempted to climb the hill, but were fiercely charged upon and forced to fall back to our first position. We tried a second time, but met the same fate; the fight then seemed to become more furious. Their leader, Ferguson, came into full view, within rifle shot as if to encourage his men, who by this time were falling very fast; he soon disappeared. We took the hill a third time; the enemy gave way.”

This battle lasted 65 minutes. Patrick Ferguson was shot and killed, and it was the first major setback for the British strategy in the South.

According to British commander Henry Clinton, the American victory “proved the first Link of a Chain of Evils that followed each other in regular succession until they at last ended in the total loss of America.”

Forty-two years later, Thomas Jefferson recalled that battle as “the joyful annunciation of that turn of the tide of success which terminated the Revolutionary War.” Indeed, Washington’s Continental Army had been fighting valiantly for five-and-half years though without decisive effect; yet, only 12 months and 12 days after the Battle of Kings Mountain, General Cornwallis would surrender his British Army to General Washington at Yorktown, Virginia. The American Revolution would soon be over.

Huzzah!