In 1682, William Penn landed on the land that became the “City of Brotherly love.” It was a city of religious tolerance. The first school in the colonies was established there in 1698, and in 1719 the city was the first to buy a fire engine. The first botanical garden, first library, and first hospital were built here in the 1700’s. It was a city that looked for ways to better itself.

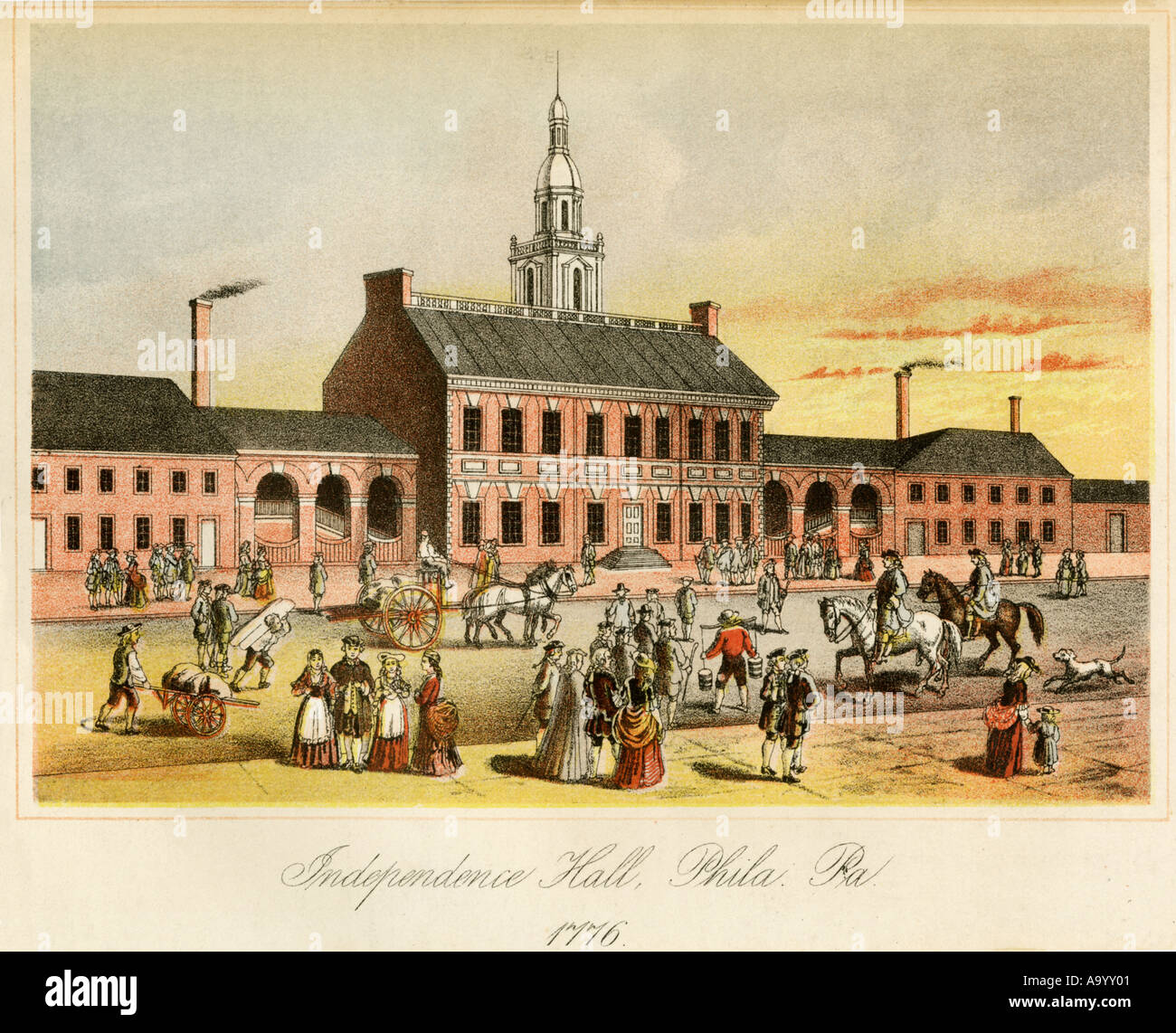

This port city of Philadelphia soon became known for its broad, tree-shaded streets, substantial brick-and-stone houses, as it continued to grow. In 1787, the wharves on the Delaware River were crowded with ships, passengers, merchants, Indians, and laborers. All interested in the imports from Europe and the West Indies.

Market Street was crowded. Women and men shopped the stores, looking for luxury items. The bakeries were busy all day, because women bought fresh bread every day; the smells of fresh bread lured the customers in.

There were open-air markets on the street that opened 3 days a week where farmers brought in their wares from the farms. They sold fresh produce, dairy goods, poultry, fish, and meat.

Dry good stores sold coffee, sugar, and spices. Also available were sundry other items. From books and spyglasses, Windsor chairs, teas from China, shoes made locally, baskets, buckets, wine and horses.

Philadelphia was the leading publishing center in America; there were 10 newspapers published in the city.

Claypoole and Dunlap published the Pennsylvania Packet and were asked to publish the first copies of the Constitution. In 1784, the Pennsylvania Packet became the first successful daily newspaper published in the US. They also printed books, proclamations, posters, and political pamphlets. Their business served as an information center. Often people gathered there to bring and exchange news. During that time in our history, the printed word was the best way to communicate over long distances.

Philadelphia boasted 33 churches, a Philosophical Society, a public Library, a museum, a poorhouse, a model jail, a model hospital, and 662 street lamps.

Taverns, inns, and beer houses were scattered around the city; most of the beer houses were on the water front. The Blue Anchor was a popular fish house that opened in 1682. The City Tavern on Second Street was new; it could accommodate 60 men overnight on its third floor. It boasted club rooms, lodging rooms, two kitchens, a bar, and a coffee room. To encourage visits, they supplied the public rooms with magazines and newspapers.

The roles of unmarried women were clearly defined. They opened their homes as boarding houses or were a school mistress in their homes. Teaching positions were also available for them as tutors in Young Ladies Academies. Women also earned money by spinning, as hat makers, and as menders. Married women ran their households.

This was the city that hosted the framers of the Constitution.

Around 40,000 people lived in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1787, as 55 delegates from twelve states gathered; Rhode Island wasn’t represented. They gathered in the same building, where many of them had signed the Declaration of Independence, worked hard on the Articles of Confederation, and now these learned men were back. As one historian noted, it was a “Convention of the well-bred, the well-fed, the well-read, and the well-wed.”

They were called framers, because this word defines their job. These men shaped, planned, and constructed a new document to govern a new country, the Constitution of the US.

The delegates all arrived and settled in boarding houses and taverns and then they went to work. Even at night, they didn’t talk about their thoughts and plans. When in the taverns or boarding houses, they were silent.

On the starting day of May 21, only eight state delegates were present, but soon others trickled in. The Convention was convened on Friday. George Washington was elected President, and the South Carolinian William Jackson was elected secretary. Elected that same day for the Committee on Rules were George Wythe from Virginia, Alexander Hamilton from New York, and Charles Pinckney from SC.

All were familiar with the two story building, the Pennsylvania State House, where they conducted their discussions and debates, because this was the same site where many of the same men wrote the Declaration of Independence eleven years earlier. This building of Georgian architecture boasted a bell tower and steeple that gave it the look of a church. That bell today is called the Liberty Bell.

It has often been remarked that in the journey of life, the young rely on energy to counteract the experience of the old. And vice versa. What makes this Constitutional Convention remarkable is that the delegates were both young and experienced. The average age of the delegates was 42 and four of the most influential delegates—Alexander Hamilton, Edmund Randolph, Gouverneur Morris, and James Madison—were in their thirties. Over half of the delegates graduated from College with nine from Princeton and six from British Universities. Even more significant was the continental political experience of the Framers: 8 signed the Declaration of Independence, 25 served in the Continental Congress, 15 helped draft the new State Constitutions between 1776 and 1780, 40 served in the Confederation Congress between 1783 and 1787, and 35 had law degrees.

George Nash has written a book about these men entitled Books and the Founding Fathers. I want to share some facts from his book.

To summarize Nash’s point: the Framers 1) read, 2) owned, 3) used, 4) created, and 5) donated books without being simply bookish or “denizens of an ivory tower.”

- John Dickinson, the person whose legacy is his August observation at the Constitutional Convention that “we should let experience be our guide” because reason may mislead us, would, at university, “read for nearly eight hours a day, dined at four o’clock, and then retired early in the evening, all the while mingling his scrutiny of legal texts with such authors as Tacictus and Francis Bacon.” William Paterson, who introduced the New Jersey Plan in June at the Constitutional Convention, in large part because it was a practical alternative to the Virginia Plan, took his college entrance examinations in Latin and Greek, and entered Princeton “at the age of fourteen. For the next four years he immersed himself in ancient history and literature, as well as such English authors as Shakespeare, Milton, Swift, and Pope.”

- Benjamin Franklin’s personal library “contained 4,276 volumes at the time of his death in 1790.” George Washington’s library at his death in 1798 contained 900 volumes, “a figure all the more remarkable since he was much less a reader than many.”

- Washington, in turn, “used” Joseph Addison’s Cato in drafting his Farewell Address. Jefferson “sent back books by the score” from Paris to Madison that, after three years of intense reading, the latter used to draft the Virginia Plan as a response to the history of failed confederacies.

- The Papers of Madison constitute “52 volumes.” The Jefferson Papers are comprised of 75 hefty volumes.”

- Finally, Franklin, Dickinson, Madison, and Jefferson were each “a faithful patron of libraries.” For example, Dickinson “donated more than 1,500 volumes to Dickinson College.”

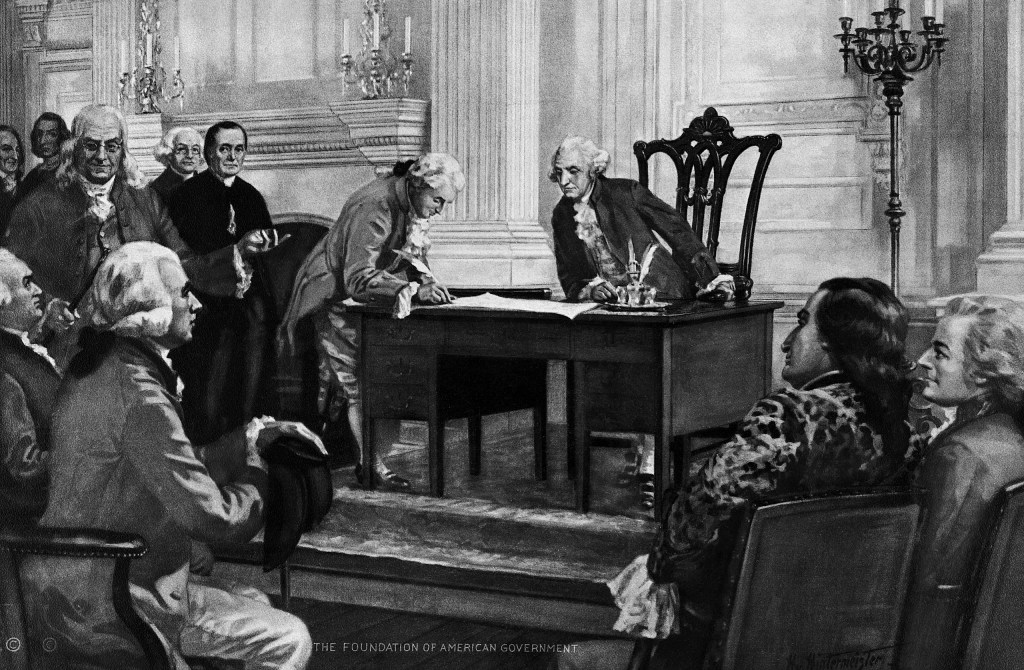

They met behind closed doors and windows in sessions to hammer out our Constitution. Reporters and visitors were banned; these leaders wanted no outside influences. Guards were placed at the doors to keep sight-seers out. James Madison was the note keeper. (We know this because his wife Dolly sold his notes to the federal government in 1837 for $30,000 after his death.)

James Madison of Virginia was a quiet fellow, but you could always tell that his mind was working and sifting through ideas. He stayed at Mrs. House’s boarding house, and he kept a candle burning all night so he could get up at any time and write down thoughts as they came to him. He told her he’d always done that. He never slept but 3 or 4 hours anyway.

Mrs. House didn’t know whether to charge him extra for all the candles. She had other boarders from Virginia, including Governor Edmund Randolph.

These dedicated men worked six days a week from 10-3 with only a 10 day break. It was during this July 4 break that James Madison and a few others put together a rough draft.

Their work took place in the Committee of Assembly Chamber Around tables laden with candlesticks, books, paper, ink wells, quill pens, and clay pipes. The newspapers printed regular articles of encouragement. Ben Franklin livened up the proceedings by using his cane to trip various delegates.

The city street commissioners had gravel put down in front of the State House to muffle the sounds of carriages and horses so as not to disturb them. Philadelphia was proud of the history being made there. In those summer months debates, bitter arguments, and compromises were on the daily docket; it was a time of hot weather and even hotter emotions.

George Washington later wrote to his friend Lafayette, “It (the Constitution) appears to me, then, as little short of a miracle.”

The American Revolution had been over for four years, and the Articles of Confederation weren’t strong enough to hold the new states together. In 1786 Alexander Hamilton called for another convention to create a stronger government.

These men called it the Grand Convention or the Federal Convention. Today its name is the Constitutional Convention. Except for Rhode Island, all states were represented. George Washington was elected President.

George Washington’s presence made the convention a prestigious event. His arrival in Philadelphia was spectacular, and a spontaneous parade quickly formed. The general was riding in his fine little coach called a chariot, and he was met by the officers of the Revolution. All those officers were joined by the Philadelphia Light Horse Company, and they rode into the city all in uniform. The city church bells were rung; some cannons were fired, and most all of Philadelphia turned out along the way to applaud the general.

He was going to stay at Mrs. House’s Boarding House, but Robert and Mary Morris insisted he be their guest. It was one of the most elegant homes in the city. Washington just took time enough to get his things in, and then he set out to pay a call on his 81 year-old friend Benjamin Franklin.

One by one the delegates arrived and began their work.

Time moved slowly during those summer months, but the men continued their meetings.

Three plans for the Constitution were looked at, and a compromise finally reached for the institution of executive, legislative, and judicial arms of government. All states would have equal representation in the Senate, and the elected officials for the House would be based on population. Even on that last day, a change was made to lower the population number for representatives.

George Washington was the first to sign his name. As the delegates moved to sign the Constitution on September 17, it was Franklin, who on the last day of the Convention said of the rising sun chair that Washington had sat in at the front of the room for four months. “During the past four months of this convention, I have often looked at the painting. And I was never able to say if the picture showed a morning sun or an evening sun. But now, at last, I know I am happy to say it is a morning sun, the beginning of a new day.”

On the night of September 17, the delegates met for one last time together at the City Tavern on Second Street to celebrate the birthplace of America’s new Government.

It seems fitting that they chose this tavern in Philadelphia. Built in 1773, many had stayed there during the First Continental Congress. A few months earlier, Paul Revere had ridden up to the Tavern with the news of the closing of the port of Boston by the British.

These leading figures of the Revolutionary War would now go back to their home states and encourage them to ratify the Constitution of the United States of America.

As James Madison proclaimed, “The happy Union of these States is a wonder; their Constitution a miracle; their example the hope of Liberty throughout the world.”

Historically, new governments come about because of war or chance. Madison’s words ring true today, as we continue to celebrate this living document.

The Framers of the American Constitution were visionaries. They designed our Constitution to endure. They sought not only to address the specific challenges facing our nation during their lifetimes, but to establish, broad foundational principles that would sustain and guide the new nation into an uncertain future, even in September, 2015.

As Samuel Adams, Harvard graduate and Sons of Liberty once said, “It does not take a majority to prevail…but rather an irate, tireless minority, keen on setting brush fires of freedom in the minds of men.”

Happy birthday to the Constitution of the United States of America!