In a few weeks, we will celebrate Thanksgiving, a national and family holiday in our country. We will gather together for fun, food, and fellowship. But will we be thankful for what we have? Will we count our blessings? Name them one-by-one? Will we serve others? Will we remember the sacrifices of those who settled our country?

“As we express our gratitude, we must never forget that the highest appreciation is not to utter words, but to live by them.”– John Fitzgerald Kennedy

Knowing nothing about the reality of the Pilgrims’ journey to America or those first years of deprivation and death, it was a fun holiday to celebrate during my younger years. At school, we would make Pilgrim and Indian hats and headpieces, eat vegetable soup and cornbread, and sing loudly, “Come Ye Thankful People Come.”

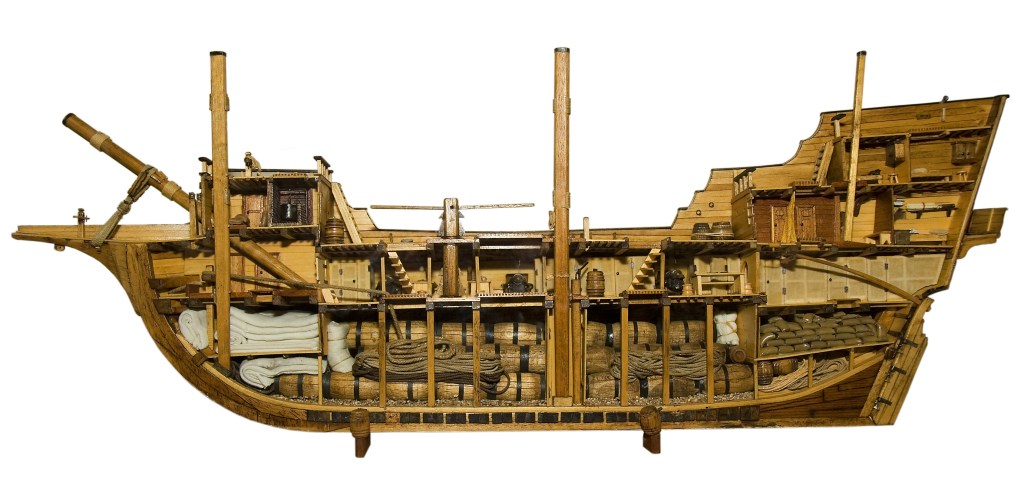

Growing up in twentieth century South Carolina, I could never have imagined this model of the insides of their ship.

The bravery of this group who was willing to give up all they knew for an unknown destination. It was their desire to worship God as they felt led that pushed them on the Mayflower.

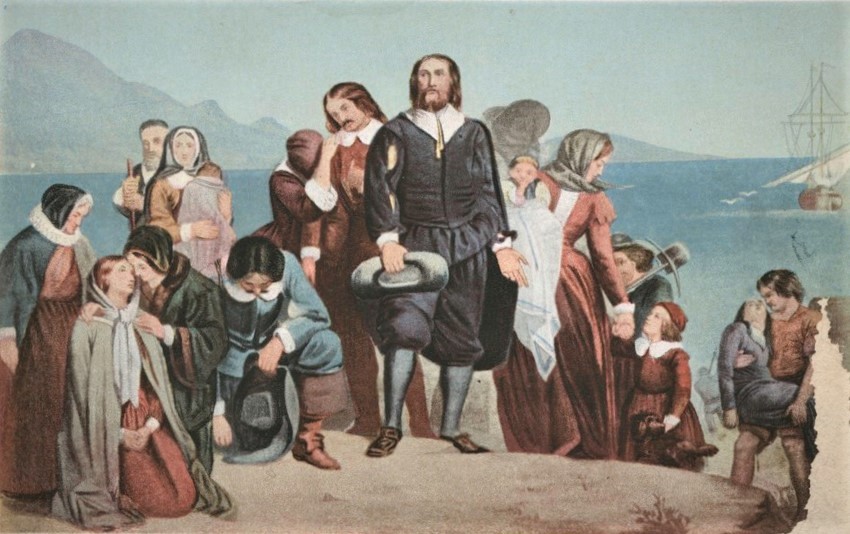

The above painting shows this group of settlers boarding their ship. On September 16, 1620, the Mayflower, no larger than a volleyball court today, sailed from Plymouth, England, bound for the Americas with 102 passengers. Headed for Virginia, storms and navigational errors pushed the Mayflower off course. And it was on November 21, they reached Massachusetts. This was the first permanent European settlement in New England.

The Embarkation of the Pilgrims (1857) by American painter Robert Walter Weir.

The painting below is a rendering of their arrival at Plymouth Rock. The faces are quite solemn and serious, as they look toward a forest and a wilderness.

The colonists began building their town. While houses were being built, the group continued to live on the ship. Many of the colonists fell ill. They were probably suffering from scurvy and pneumonia caused by a lack of shelter in the cold, wet weather. Although the Pilgrims were not starving, their sea-diet was very high in salt, which weakened their bodies on the long journey and during that first winter.

As many as two or three people died each day during their first two months on land. Only 52 people survived the first year in Plymouth. More than half of the heads of households died. Five of the eighteen wives lived through the scourges of pneumonia, tuberculosis, and scurvy.

“…Aboute no one, it began to raine…at night. It did freee &snow …still the cold weather continued…very wet and rainy, with the greatest gusts of wind ever we saw…frost and foule weather hindered us much; this time of the yeare seldom could we worke half the week.”

On March 24, a journal entry sums their situation up: “Dies Elizabeth, the wife of Mr. Edward Winslow. N.B. This month thirteen of our number die. And in three mons past dies halfe our company…Of a hundred persons, scarce fifty remain, the living scarce able to bury the dead.”

What a courageous group of men, women, and children; there are no words to laud their fortitude. During the third week of March, the weakened survivors from the Mayflower rowed ashore to their new homes in New Plimouth in those huts that needed rebuilding.

The earliest houses in Plymouth had thatched roofs, but because they were more likely to catch on fire, the colony eventually passed a law that required new homes be built with plank instead. Most houses had dirt floors, not wooden floors, and each had a prominent fire and chimney area, since this was the only source of heat as well as the only way to cook. Each house would have had its own garden, where vegetables and herbs could be grown. Each family was also assigned a field plot just outside of town, where they could grow corn, beans, peas, wheat, and other crops that required more space to grow, as well as to raise larger livestock.

Still, God’s grace was sufficient. English-speaking Indians named Samoset and Squanto helped the Pilgrims learn how to farm the land and harvest the bay. Squanto lived with the Pilgrims until 1622 when he died. His last request was that Gov. William Bradford would pray that he might go to the Englishman’s God in heaven. Bradford wrote: “Squanto continued with them and was their interpreter, and was a special instrument sent of God for their good beyond their expectation. He directed them how to set their corn, where to take fish and to procure other commodities and was also their pilot to bring them to unknown places for their profit, and never left them till he dyed.”

By 1621, passenger Edward Winslow wrote a letter in which he said “we have built seven dwelling-houses, and four for the use of the plantation.” In 1622, the Pilgrims built a fence around the colony for their better defense–the perimeter was nearly half a mile, and the fence was about 8 to 9 feet high.

They could have given up and returned to England. They could have thrown up their hands in despair. But their faith was in God, and they chose to not let the hardships make them bitter. Their trust laid the enduring foundations of our country America, and they were thankful.\A pilgrim is a person who goes on a long journey often with a religious or moral purpose, and especially to a foreign land.

After the Mayflower arrived, the first baby born was a boy. His parents (William and Susannah White) named him Peregrine – a word which means traveling from far away and also means pilgrim. Governor William Bradford wrote, “They knew they were pilgrims, and looked not much on those things, but lifted up their eyes to the heavens, their dearest country; and quieted their spirits.”

This beautiful cradle is believed to have been brought on the Mayflower by William and Susanna White, for the use of Peregrine White, who was born onboard the ship in November 1620 while it was anchored off the tip of Cape Cod. It is on display at the Pilgrim Hall Museum in Plymouth.

These few fought, fell, and rose to fight again against wild animals, extreme weather, poor housing, and a starvation diet. Then they intentionally celebrated a day of thanksgiving after a time of such hardship. Long-time chronicler and governor William Bradford described this celebration in 1621 with these words.

They began now to gather in the small harvest they had, and to fit up their houses and dwellings against winter, being all well recovered in health and strength and had all things in good plenty. For as some were thus employed in affairs abroad, others were exercising in fishing, about cod and bass and other fish, of which they took good store, of which every family had their portion. All the summer there was no want; and now began to come in store of fowl, as winter approached, of which this place did abound when they came first (but afterward decreased by degrees). And besides waterfowl there was great store of wild turkeys, of which they took many, besides venison, etc. Besides they had about a peck of meal a week to a person, or now since harvest, Indian corn to that proportion. Which made many afterwards write so largely of their plenty here to their friends in England, which were not feigned but true reports.

“It is therefore recommended . . . for solemn thanksgiving and praise, that with one heart and one voice the good people may express the grateful feelings of their hearts and consecrate themselves to the service of their divine benefactor . . . .”– November 1, 1777 (adopted by the 13 states as the first official Thanksgiving Proclamation) – Samuel Adams

For more information about our forefathers, look at MayflowerHistory.com.

Abigail Adams

Abigail Adams